Modeling binary choice data

Source:vignettes/modeling-binary-choice-data.Rmd

modeling-binary-choice-data.RmdClassic methods

For binary choice data not explicitly designed to titrate out indifference points (as in an adjusting amount procedure), there are a few widely-used traditional scoring methods to quantify discounting.

Kirby scoring

One scoring method is the one designed for the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (Kirby, 1999):

data("td_bc_single_ptpt")

mod <- kirby_score(td_bc_single_ptpt)

print(mod)

#>

#> Temporal discounting indifference point model

#>

#> Discount function: hyperbolic, with coefficients:

#>

#> k

#> 0.02176563

#>

#> ED50: 45.9439876371218

#> AUC: 0.0551987542147013Although this method computes

values according to the hyperbolic discount function, in principle it’s

possible to use the exponential or power discount functions (though this

is not an established practice and should be considered an experimental

feature of tempodisco):

mod_exp <- kirby_score(td_bc_single_ptpt, discount_function = 'exponential')

print(mod_exp)

#>

#> Temporal discounting indifference point model

#>

#> Discount function: exponential, with coefficients:

#>

#> k

#> 0.008170247

#>

#> ED50: 84.8379742026149

#> AUC: 0.0335100135964859

mod_pow <- kirby_score(td_bc_single_ptpt, discount_function = 'power')

print(mod_pow)

#>

#> Temporal discounting indifference point model

#>

#> Discount function: power, with coefficients:

#>

#> k

#> 0.3052023

#>

#> ED50: 8.69012421478859

#> AUC: 0.1173431135372Wileyto scoring

It is also possible to use the logistic regression method of Wileyto et al. (2004), where we can solve for the value of the hyperbolic discount function in terms of the regression coefficients:

mod <- wileyto_score(td_bc_single_ptpt)

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

print(mod)

#>

#> Temporal discounting binary choice linear model

#>

#> Discount function: hyperbolic from model hyperbolic.1, with coefficients:

#>

#> k

#> 0.04372626

#>

#> Call: glm(formula = fml, family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = data)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> .B1 .B2

#> 0.49900 0.02182

#>

#> Degrees of Freedom: 70 Total (i.e. Null); 68 Residual

#> Null Deviance: 97.04

#> Residual Deviance: 37.47 AIC: 41.47Newer methods

Linear models

The Wileyto et al. (2004) approach turns out to be possible for other discount functions as well (Kinley, Oluwasola & Becker, 2025.):

| Name | Discount function | Linear predictor | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

hyperbolic.1 |

Hyperbolic (Mazur,

1987): |

||

hyperbolic.2 |

(Mazur,

1987): |

||

exponential.1 |

Exponential (Samuelson,

1937): |

||

exponential.2 |

Exponential (Samuelson,

1937): |

||

power |

Power (Harvey,

1986): |

||

scaled-exponential |

Scaled exponential (beta-delta; Laibson,

1997): |

, | |

nonlinear-time-hyperbolic |

Nonlinear-time hyperbolic (Rachlin,

2006): |

, | |

nonlinear-time-exponential |

Nonlinear-time exponential (Ebert & Prelec,

2007): |

, |

Where is the logit function, or the quantile function of a standard logistic distribution, and is the quantile function of a standard Gumbel distribution.

We can test all of these and select the best according to the Bayesian Information Criterion as follows:

mod <- td_bclm(td_bc_single_ptpt, model = 'all')

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

print(mod)

#>

#> Temporal discounting binary choice linear model

#>

#> Discount function: exponential from model exponential.2, with coefficients:

#>

#> k

#> 0.01003216

#>

#> Call: glm(formula = fml, family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = data)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> .B1 .B2

#> 3.597 -16.553

#>

#> Degrees of Freedom: 70 Total (i.e. Null); 68 Residual

#> Null Deviance: 97.04

#> Residual Deviance: 15.7 AIC: 19.7Nonlinear models

To explore a wider range of discount functions, we can fit a

nonlinear model by calling td_bcnm. The full list of

built-in discount functions is as follows:

| Name | Functional form | Notes |

|---|---|---|

exponential (Samuelson, 1937) |

||

scaled-exponential (Laibson, 1997) |

Also known as quasi-hyperbolic or beta-delta | |

nonlinear-time-exponential (Ebert & Prelec,

2007) |

Also known as constant sensitivity | |

dual-systems-exponential (Ven den Bos & McClure,

2013) |

||

inverse-q-exponential (Green & Myerson,

2004) |

Also known as generalized hyperbolic (Loewenstin & Prelec), hyperboloid (Green & Myerson, 2004), or q-exponential (Han & Takahashi, 2012) | |

hyperbolic (Mazur, 1987) |

||

nonlinear-time-hyperbolic (Rachlin, 2006) |

Also known as power-function (Rachlin, 2006) | |

additive-utility (Killeen, 2009) |

Here, is the value of the delayed reward. For , . | |

power (Harvey, 1986) |

mod <- td_bcnm(td_bc_single_ptpt, discount_function = 'all')

print(mod)

#>

#> Temporal discounting binary choice model

#>

#> Discount function: exponential, with coefficients:

#>

#> k gamma

#> 0.01083049 0.09341821

#>

#> Config:

#> noise_dist: logis

#> gamma_scale: linear

#> transform: identity

#>

#> ED50: 63.9996305466619

#> AUC: 0.0252791100912786

#> BIC: 25.9537097154224Choice rules

Several additional arguments can be used to customize the model. For example, we can use different choice rules—the “logistic” choice rule is the default, but the “probit” and “power” choice rules are also available (see this tutorial for more details):

Error rates

It is also possible to fit an error rate that describes the probability of the participant making a response error (see Vincent, 2015). I.e.: where is the probability of choosing the immediate reward, is the link function, and is the linear predictor.

data("td_bc_study")

# Select the second participant

second_ptpt_id <- unique(td_bc_study$id)[2]

df <- subset(td_bc_study, id == second_ptpt_id)

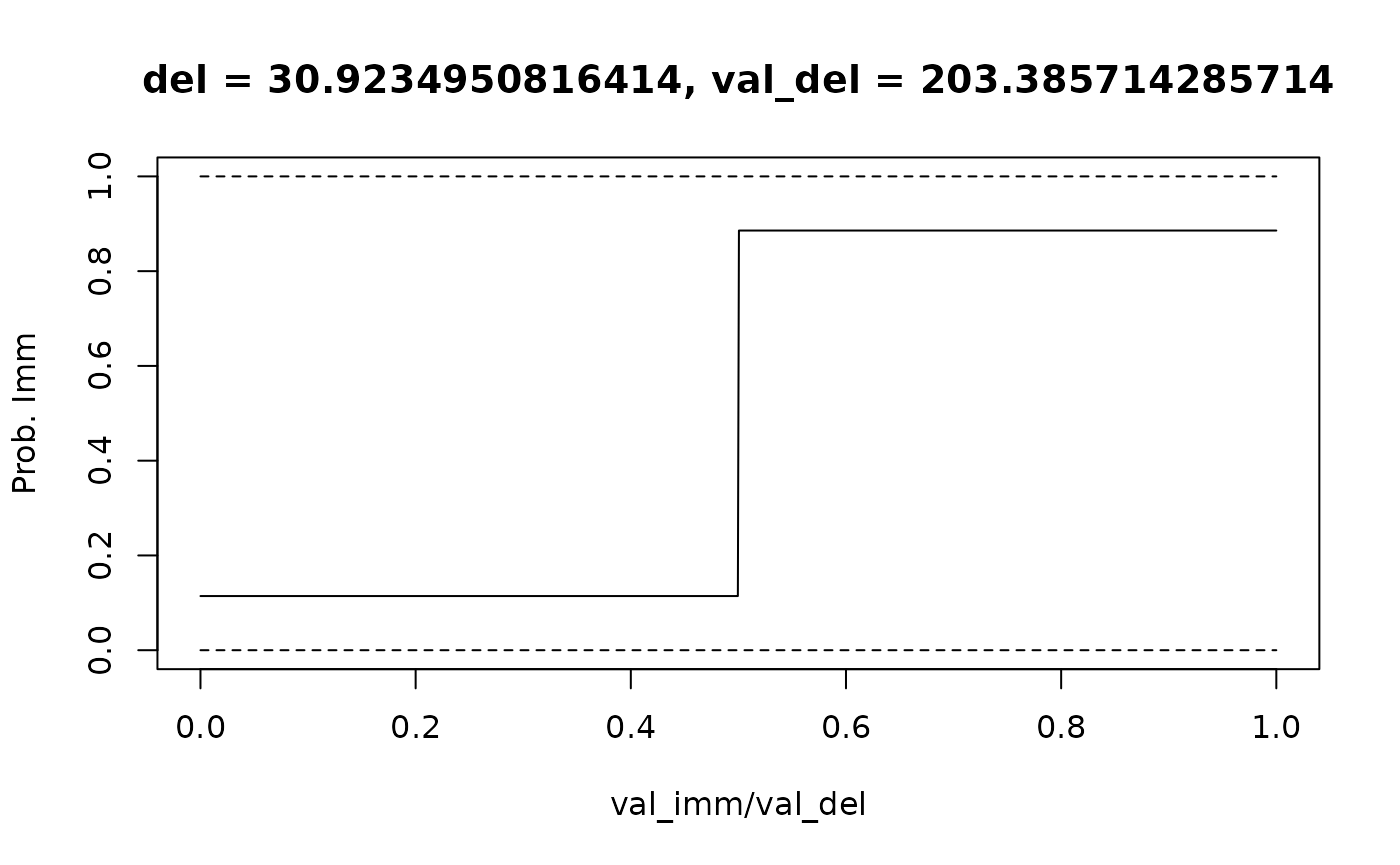

mod <- td_bcnm(df, discount_function = 'exponential', fit_err_rate = T)

plot(mod, type = 'endpoints', verbose = F)

lines(c(0, 1), c(0, 0), lty = 2)

lines(c(0, 1), c(1, 1), lty = 2)

We can see that the probability of choosing the immediate reward doesn’t approach 0 or 1 but instead approaches a value of .

Fixed endpoints

Alternatively, we might expect that participants should never choose

an immediate reward worth 0 and should never choose a delayed reward

worth the same face amount as an immediate reward (Kinley, Oluwasola &

Becker, 2025; see here

for more details). We can control this by setting

fixed_ends = T, which “fixes” the endpoints of the

psychometric curve, where val_imm = 0 and

val_imm = val_del, at 0 and 1, respectively:

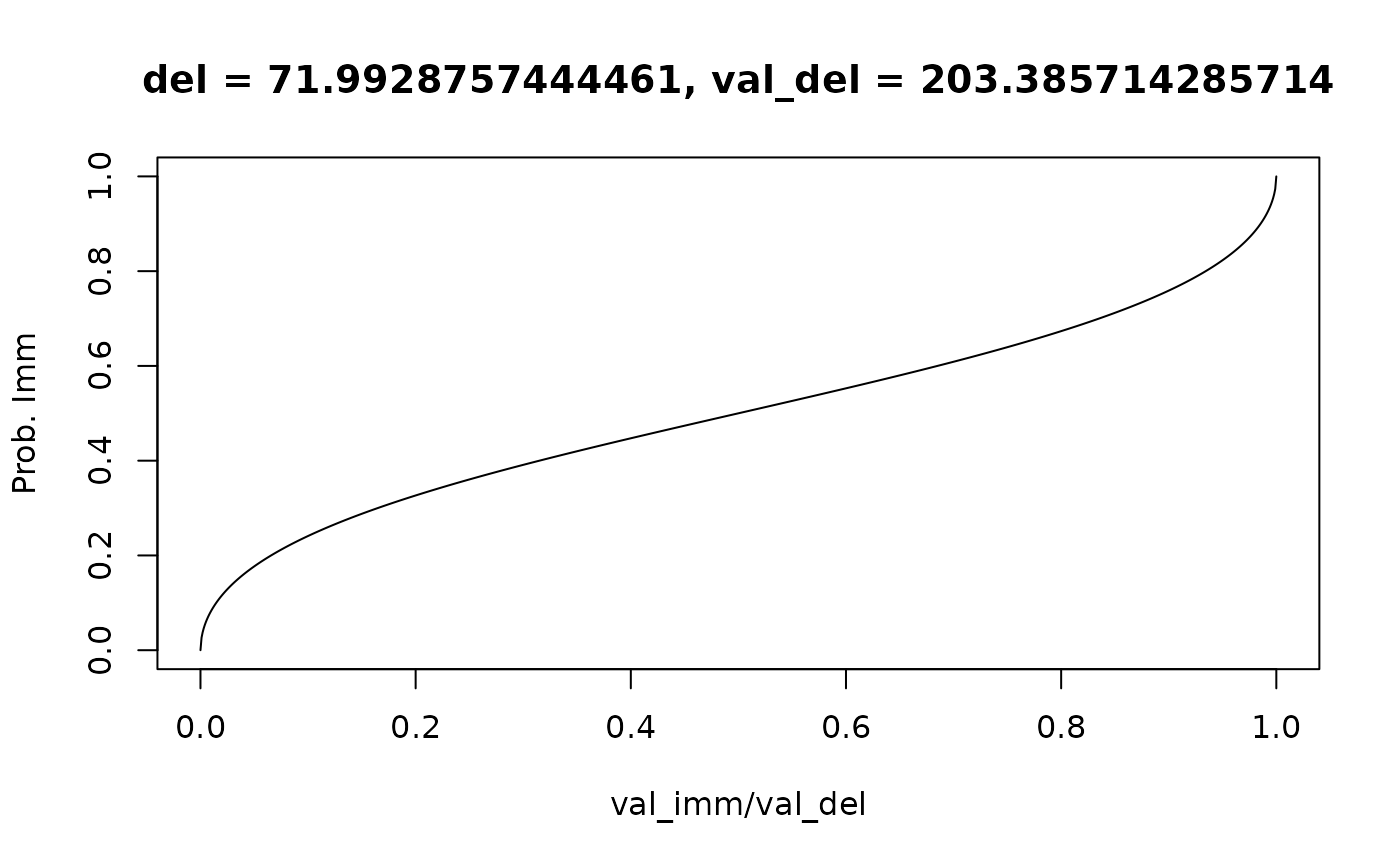

mod <- td_bcnm(df, discount_function = 'exponential', fixed_ends = T)

plot(mod, type = 'endpoints', verbose = F, del = 50, val_del = 200)